Language

|

Beauty & a key

to knowledge

|

-

-

Wikipedia articles:

Istro-Romanian language

Transylvanian Saxons

Papiamento

Saterland Frisian

Introduction

Well, we have had Ligurian in Sardinia and Occitan in Calabria, but there are plenty more strange little pockets of languages which seem to be out of place. Some have been created by people moving from their homelands for political, religious or economic reasons, but others are survivals in remote areas of languages once more widely spoken which have been swept away in other areas by historical events. Why are there Romanian speakers close to the Adriatic in an area dominated by Slavonic speech? How did German speakers come to settle at the far end of Transylvania? Why did Portuguese become an element in a creole spoken in a Dutch possession surrounded by English- and Spanish-speaking territories? And how did the East Frisian language survive in the countryside of north-western Germany, well inland from the area where it developed, when it has been replaced there by Low Saxon dialects? The answers to such questions are not always known, and so sometimes we can only speculate on how these strange anomalies arose.

Istria

Istria is a peninsula in the Adriatic, just south of Trieste. Between the wars it was part of Italy, but it is now (2017) divided between Slovenia, Croatia and Italy. Not surprisingly, most people use one of the national languages, but some speak a local dialect of the Venetian language and there is also an indigenous language called Istriot. Linguists disagree about the classification of this, but I am inclined to the view that it is either the last surviving form of the Dalmatian language or was once part of a language continuum which included Dalmatian and the Rhaeto-Romance languages.

However, what intrigues me most is the presence of an East Romance language, quite distinct from the other Romance languages spoken in the region.

Istro-Romanian

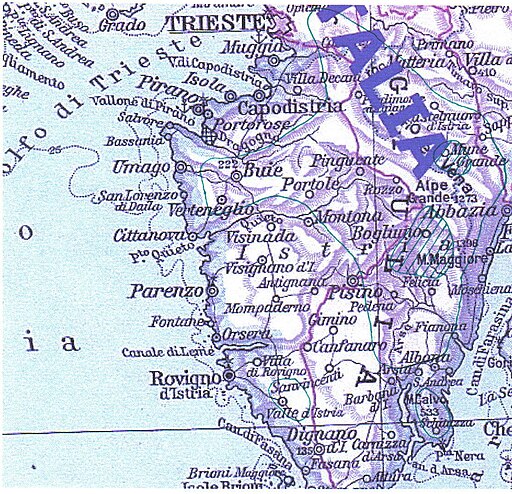

Istro-Romanian is a distinct variety of Romanian which has been present in Istria for many centuries. It was once more widely spoken, but is now confined to a few areas of north-eastern Istria. Exactly how and when it arrived in the peninsula is a matter for some debate.

|

Map of Istria showing former and

present extent of Istro-Romanian[1]

(Public Domain) |

Various theories have been put forward and are discussed in the Wikipedia article, but there is inadequate evidence to draw any firm conclusion. There is a theory that the language is an amalgam of Latin-derived dialects present since the time of the Roman Empire and varieties of East Romance brought by shepherds from the southern Balkans who were fleeing from the Ottoman Turks. However, this seems unlikely to me. The language differs markedly from the other Romance languages spoken in the region and is closer to Daco-Romanian, the principal variety used in modern-day Romania, than to the more southerly varieties. The more likely theory is that the Istro-Romanians migrated westward from Țara Moților in Transylvania some time in the Middle Ages. This idea is supported by evidence from folklore experts. Why they would have migrated is not at all clear, but maybe they came for economic or political reasons. Perhaps they sought less harsh climatic conditions or a less harsh political regime.

Notes

-

The green line shows the extent of the language round about 1800 and the hatched areas show

where it was still in use round about 1900. If you have difficulty viewing the map, enlarge it by

clicking in the image. Clicking again and then a third time will enlarge it further.

The Transylvanian Saxons

|

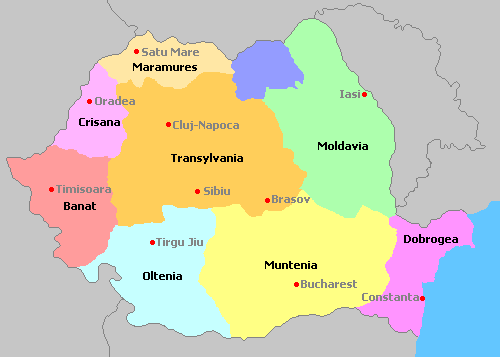

Regions of Romania[1]

(Wine and Vine Search website)

|

Transylvania became part of Romania after the break-up of the Habsburg empire at the end of World War I. For centuries the region had been part of Hungary, as had other parts of northern and western Romania. While a large part of the region is Romanian-speaking, a substantial area of Hungarian speech is stranded more or less in the centre of the enlarged country, and this has caused a certain amount of friction over the years. The linguistic map below shows this area, but it also reveals the linguistic diversity of Romania and in this section I am concentrating on one of the other linguistic minorities.

|

Linguistic map of Romania 2012[2]

(SB Language Maps - WordPress.com) |

There are several small pockets of German speech in Romania and in the north and west we find some varieties of Swabian, but in Transylvania the dialects used are Franconian. So it is strange that the German speakers are called Transylvanian Saxons, but the word Saxons seems to have been applied indiscriminately to Germans in the old Kingdom of Hungary, probably because Saxons were employed in the Hungarian chancellery. Germans were originally brought to Transylvania in the 12th century to defend the south-eastern border of the Kingdom of Hungary, but later settlement was for economic reasons. The Germans were brought in because they had skills useful to Hungary,

|

Panorama of Sibiu

(Photo: Amorphisman at Wikimedia Commons) |

for example in the field of mining, and they played a major role in the development of cities such as Sibiu and Brașov, the centres of which still have a German feel about them. However, since World War II a great many German speakers have emigrated, mainly to Germany and Austria, but also to North America. In 1930 there were approximately three quarters of a million Germans in Romania, including the Swabians in the west and north, but by 2010 the number remaining was just a few tens of thousands.

Incidentally, the current President of Romania (2017) is Klaus Iohannis, a Transylvanian Saxon who was formerly the elected mayor of Sibiu.

See also: Wikipedia article on Germans of Romania

Notes

-

For the record, the small unmarked area is part of Bukovina.

-

Repeated clicking in the map works for this one too.

A little anecdote

I chat online with all sorts of people in various parts of the world and they often come up with surprises. One day I happened upon a young woman whose photo showed her to be tall, fair and blue-eyed. Her profile said that she spoke English and German. I asked her where she came from and was expecting her to name a place somewhere in Germany, but her reply was "Romania".

"Are you a Transylvanian German?" I asked.

"Yes," she replied, "You know about us then."

So I have had a conversation with one of the remaining descendants of those medieval German settlers.

Papiamento

|

Dutch neatness in Willemstad

(Evandria at Wikimedia Commons) |

Some time back it struck me that it was odd that the Dutch island of Curaçao, off the coast of Spanish-speaking Venezuela, should have a name that looked Portuguese - it was the cedilla that jumped out at me. I eventually got round to researching this and found that the story is very complicated and that the Dutch ABC islands, Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao, have a language of their own. It is called Papiamento, or Papiamentu, and its origins are not fully understood.

The various theories about its origins are discussed in this Wikipedia article and I think the similarities to Cape Verdean Creole, a Portuguese-based creole language, could be significant, but there has been a great deal of contact with other languages, including the Romance varieties spoken by Iberian Jews who sought refuge in the area from political turmoil.

See also these Wikipedia articles:

Saterland Frisian

|

Bilingual road sign

(Local name on second line) |

The East Frisian dialects were once spoken in the far north-east of the Netherlands and in an area of north-western Germany, but they have now been replaced in these areas by Gronings and East Frisian Low Saxon. The only surviving East Frisian dialect is spoken well to the south of the original range of the language and is known as Saterland Frisian. So how did this strange situation come about?

Well, according to Wikipedia:

The last remaining living remnant of Old East Frisian is an Ems Frisian dialect called Sater Frisian or Saterlandic (its native name being Seeltersk), which is spoken in the Saterland area in the former State of Oldenburg, to the south of East Frisia proper. Saterland (Seelterlound in the local language), which is believed to have been colonised by Frisians from East Frisia in the eleventh century, was for a long time surrounded by impassable moors. This, together with the fact that Sater Frisian always had a status superior to Low German among the inhabitants of the area, accounts for the preservation of the language throughout the centuries.

Another important factor might be that after the Thirty Years' War, Saterland became part of the bishopric of Münster. As a consequence, it was brought back to the Catholic Church, resulting in isolation from the principal Protestant part of East Frisia since about 1630, so marriages were no longer contracted with people from the north.

Other strange survivals

Basque

|

Location map - Basque Country

(By Eddo at Wikimedia Commons) |

The Basque language is a champion survivor. It is used in an area astride the Franco-Spanish border at the western end of the Pyrenees and its origins are the subject of much controversy, but there is no doubt about its longevity. The most likely theory is that it is an "orphan language", the sole survivor of a family of languages spoken in western Europe before the arrival of the Indo-European languages which now dominate the region. Some perceptive linguists feel they have detected similarities to the Caucasian languages, also thought to have been present at the other end of Europe before the Indo-European expansion, and so it is possible that both they and Basque belong to a superfamily of languages once spread right across Europe. Be that as it may, Basque continues to exist, surrounded by Romance languages which arrived as Latin about 2,000 years ago and have failed to swamp it.

Basque is very different from the other indigenous languages of western Europe. The Indo-European languages are of the nominative-accusative type, whereas Basque is ergative–absolutive. This means that, whereas we are used to treating the subjects of verbs as nominative, whether the verbs are transitive or intransitive, Basque puts the subject of an intransitive verb and the object of a transitive verb in the absolutive and the subject of a transitive verb in the ergative. This is a quite different way of looking at the world.[1] Moreover, verbs are organized in Basque in a very complex way. Few are synthetic and far more are periphrastic. The concepts of tense and mood are merged, so that a grammar will refer to "tenses" (in quotation marks). And, most bewildering for the outsider, a verb can agree in person and number with the subject, with a direct object and with any indirect object which happens to be around. This gives rise to a vast number of verb forms, which vary from each other by the addition of prefixes, suffixes and infixes. The utterly brilliant or the sadomasochistic might wish to tackle this article on Basque verbs.

Notes

- Imagine that a dog is lying on a carpet. It gets up and moves to a different position. Both n.-a. and e.-a. languages would say something like "The dog moved". However, suppose its owner picked it up and then moved it to another position for whatever reason. N.-a. languages would say "The owner moved the dog". E.-a. languages would say something which actually means "The dog moved by the agency of the owner".

Lipovan Russian

|

Romanian Dobruja

- detail of map dated 2012

(SB Language Maps)

|

In the 17th century reforms were undertaken in the Russian Orthodox Church to bring its practices in line with those of the mainstream Orthodox Church. However, traditionalists objected to the reforms and some refused to change their ways. Eventually the old practices were banned and many of the dissenters moved elsewhere in order to be able to observe the old rites. In the 18th century some settled in territory now in Romania and there continues to be a community of Russian-speaking Lipovans, as they are called, in Dobruja in south-eastern Romania. The dissenters are also referred to as Old Believers and there is a

Wikipedia article with that name.

The Romanian state now acknowledges the Russian Orthodox Old-Rite Church and the Lipovan community and its language.[1] There is also a

political party representing its interests.[2]

The linguistic map specifically shows Lipovan Russian as one of the minority languages of Romania. I have not been able to ascertain how it differs from standard Russian, but I think that, given the conservative tendencies of its speakers, it is likely that it is somewhat archaic.

For a more thorough version of the story, see this article on the Lipovan Russians.

Notes

- See this quotation from pustakalaya.org on Russian language:

The language has a co-official status ... in seven Romanian communes in Tulcea and Constanţa counties. In these localities, Russian-speaking Lipovans, who are a recognized ethnic minority, make up more than 20% of the population. Thus, according to Romania's minority rights law, education, signage, and access to public administration and the justice system are provided in Russian alongside Romanian.

- The Wikipedia article insists on spelling Lipovan with double p, but I have no idea why.

- Posted May - October 2017

For reference, as webpage appears dead.

Fuller text found on http://pustakalaya.org/wiki/wp/r/Russian_language.htm:

Russian-language schooling is also available in Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania, but due to education reforms, a number of subjects taught in Russian are reduced at the high school level. The language has a co-official status alongside Moldovan in the autonomies of Gagauzia and Transnistria in Moldova, and in seven Romanian communes in Tulcea and Constanţa counties. In these localities, Russian-speaking Lipovans, who are a recognized ethnic minority, make up more than 20% of the population. Thus, according to Romania's minority rights law, education, signage, and access to public administration and the justice system are provided in Russian alongside Romanian. In the Autonomous Republic of Crimea in Ukraine, Russian is an officially recognized language alongside with Crimean Tatar, but in reality, is the only language used by the government, thus being a de facto official language.

- Added April 2018